Our History

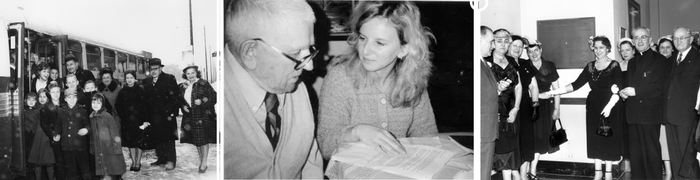

The year was 1922. For immigrants in the U.S., life was especially harsh. Work was hard to find. Once obtained, the job provided few rewards. Hours were long, pay was meager and management could always replace you with someone who would work for less. Many things could and did go wrong. People died. Spouses sought solace in alcohol. Step-parents preferred their natural children over those of their mate. Youngsters quickly learned that a shoplifted vegetable tasted better than no food at all. Authorities could not cope with people who did not speak English. Fortunately, there were established Polish Americans living in Chicago who saw all this and wanted to help. Who were these people? They were the Who's Who of Polonia.

They were the members of The Chicago Society of the Polish National Alliance. As leading citizens of Chicago, active in politics, government, business and education, these men were the doers who routinely made things happen. Most of all, they were the ones who cared, who realized that ignoring the ills of society only intensifies problems.

On August 16, 1922, due to the efforts of The Chicago Society, Polish Welfare Association was incorporated as a nonprofit organization. Officially, delinquency was the reason for its existence. The Jackroller, a book written in 1930 by Dr. Clifford R. Shaw, head of the department of sociology, Illinois Institute of Juvenile Research, profiles the delinquent of the time. In this real life history, Stanley, the son of Polish immigrants, admits to being a runaway, vagrant, beggar, truant, shoplifter, petty thief, railroad thief, burglar and jackroller. As a result of these behaviors from ages 6 to 18, Stanley spends much of his young life in police stations, the Juvenile Detention Home, Chicago Parental School, St. Charles School for Boys, Illinois State Reformatory at Pontiac and the Chicago House of Correction.

The Chicago Society members were determined to prevent a proliferation of Stanleys. It was generally agreed that the problem of juvenile delinquency must be attacked early and in the home -- a task which could be accomplished with a measure of success only by a Polish agency, stated Merril F. Krughoff, a graduate student at the University of Chicago, in a report on The Polish Welfare Association of Chicago, dated Aug. 1, 1934. Julius F. Smietanka, an attorney, a member and eventual president of the Chicago School Board and the first president of Polish Welfare Association, is credited with insisting that the fledgling organization emphasize professionalism. Krughoff cites his sympathy with social service objectives in the larger community and his continuous efforts to keep abreast of developments in the profession.

The Chicago Society News, dated March 1924, carried an article written by T. J. Szmergalski, superintendent of recreation centers of the West Park System and Secretary of Polish Welfare Association. In it he hints at how Smietanka achieved his objectives: Accordingly, on November 15th, of last year, quarters were opened at 308 N. Michigan blvd., with Mrs. T. Sakowska, creditably known among the Poles of Chicago for her many volunteer efforts in social and welfare service, as Superintendent, and Miss Zajaczkowska, as Stenographer. The building in which we are housed contains the offices of sixteen American social and welfare agencies, such as the United States Charities, Infant Welfare, etc., and since our opening we have handled a number of juvenile and adult delinquent cases, as well as a number of general welfare cases of some importance. Szmergalski's final comment sounds perfectly appropriate today: By working quietly, cautiously and effectively we hope to win the confidence of the English and Polish public, and hope thereby to have the results achieved speak for us. A stable and reliable foundation for a permanent existence will thus be laid.

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 is notorious. People went from riches to rags seemingly overnight. But what about those who had already been in rags before Black Tuesday? What about Polish Welfare Association, a seven year-old institution devoted to the social welfare of Polish American immigrants and their families? Just five years earlier, an article about PWA in the March 1924 issue of The Chicago Society News stated, Financial support is necessary but this we plan to secure by building up a reputation for unbiased, impartial, honest, sincere, intelligent, prompt, reliable, constructive and effective social service. And sufficient support had indeed been realized. Ably run for three years by volunteer Mary Sakowska, PWA achieved in 1925 that vision of professionalism which had been first articulated by President Julius F. Smietanka. Appointed superintendent during October, Mary Midura brought to PWA from Connecticut a total of 15 years of experience in social work. Her expertise with agencies in the fields of probation, family welfare, child welfare and immigrant protection translated readily to the Midwest. By 1926 PWA was granted membership in the Council of Social Agencies.

By the early part of 1930 Miss Midura had a professional staff consisting of two case workers and one part time case work aide. In a story dating from February, 1927, Miss Midura indicated how Polish Welfare Association succeeded in preventing delinquency in two boys: A widow reported to Juvenile Court that her sons, aged 14 and 15, were abusive to her. When the court placed them on probation, the case came to PWA's attention. Investigation revealed the charges were without foundation and the mother had other interests which explained her hostility to her sons. PWA's discoveries led to the appointment of a guardian for the boys. Medical examination revealed the boys were suffering from malnutrition. Ultimately, both boys were restored to health and were very happy in their new home. That same year, in addition to the 59 cases handled in Juvenile Court, PWA was involved with 89 cases heard in either the Court of Domestic Relations, Boy's Court, Municipal Branch Court, Indifferent Parent's Court or Federal Court. Still, Miss Midura deplored the fact that some 1000 cases of Polish youth handled in Juvenile Court in 1926 and 1927 could not be addressed for lack of staff. As had been predicted in that early Chicago Society article, financial support was crucial. In 1928 PWA's annual budget was approximately $12,000. Perhaps a good portion of that operating capital was garnered on Wednesday, January 18, 1928, when one could attend a formal reception and benefit ball at the New Stevens Hotel Grand Ballroom (Michigan Ave. at 7th Street) for a $2.50 subscription fee. Although there is no record of attendees, the engraved invitation lists 253 individuals who held committee assignments for the event. But those good times did not last.

The stock market crash and the bank failures of 1931 caused many prominent Poles to lose their savings. Contributions to PWA dwindled; staff could not always be paid. Despite these hardships, Miss Midura and one case worker, the others having resigned, continued to do all they could. By 1933 the annual budget had dropped to $2000. The time was called The Great Depression, and the outlook was indeed depressing. PWA services, although still desperately needed, were drastically curtailed. However, service was never eliminated. On a veritable shoestring, PWA continued to help the neediest, always looking for better times, always hoping for resurgence. Reorganization actually came about in 1934. But that is another story. In 1933 and 1934 the Century of Progress International Exposition attracted thousands to Chicago. WGN became known for broadcasts from the dance floor of the Blackhawk. And no people were more active than the Polish American community. Second-generation Poles started to think about single family homes and began a migration outwards along Milwaukee and Archer avenues. Yet the original settlements (Polish Downtown, St. Adalbert's, Bridgeport, Back of the Yards and South Chicago) remained the base of the immigrant and first-generation population. There was a comfort level to living where jobs, church and school reflected blood and ethnic relationships. The family survived almost as though it were part of a Polish village that had been relocated to urban America. Immigrants did not need to learn English well since shop signs and newspapers were written in Polish. Nor did they need to travel out of the neighborhood since doctors, fraternal groups and even funeral chapels were available within the walking-city. There also was stress from overcrowding, potential closings of steel mills and packing plants, the availability and acceptance of alcohol as a means of coping, and technological change as measured by the number of telephones and cars.

Poles were beset. Staying in ethnic areas made Americanization more difficult; moving made the importance of money and its acquisition eclipse the richer values of family life. Polish Welfare Association was as necessary as ever. Merril F. Krughoff, a graduate student at the University of Chicago, in a report on PWA dated Aug. 1, 1934, suggested that Mary Midura, its first superintendent, identified the following challenges: First, and most important is casework service. Second is the interpretive service by which family welfare and other agencies are aided in their work with the Polish group. Third, various kinds of educational and publicity work are sponsored by the Association. Fourth, the Association helps promote high grade recreational and group work. In order to best reach those in need, PWA adopted a District Committee model of management, with caseworkers visiting various parts of the city. The newer Polish areas, specifically Cragin-Hanson Park, Avondale, Portage Park, and Brighton Park, were added to the five neighborhoods mentioned above. Complaints would be heard regularly, perhaps one or two evenings per week in each district. Most were resolved by immediate advice, information or referrals; some were taken on as cases for PWA management. For example, the Infant Welfare Society referred a family to PWA because of domestic discord. The man came to America as a child, but met and married his wife while visiting Poland. His mother always sided with him, even though he drank heavily and provided insufficient money to run the house. Furthermore, his wife spoke no English, had no friends and was physically and verbally abused.

While the outcome of this particular case is not recorded, Krughoff indicates that PWA regularly bridged the gap between Poles and the community at large. Articles placed in Polish newspapers often addressed American standards of education and childcare, exploitation by unethical lawyers and the tendency to value home ownership more than family life. Through such efforts, PWA won support for its work, both in the Polish American community and in the broader social service community. Soon, however, there were to be more problems. The rumblings of war had widespread echoes. In Polish America in Transition: Social Change and the Chicago Polonia, 1945-1980 Dominic A. Pacyga states: World War II proved to be a watershed in the history of Polonia. It had a tremendous acculturating effect on Polish Americans. At the same time it brought a renewed immigration that pumped fresh blood into the struggling ethnic consciousness and rejuvenated Polish neighborhoods, at least for a short while. Change was on the way, and in the already established tradition, PWA was ready to embrace that change. Freedom has been a rallying cry for Poles throughout history. The baptism of Duke Mieszko in 966 ensured independence from Germany and marked the official founding of Poland. In the 14th century, Casimir III the Great established Poland as a haven for Jews. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Poland was the only country without religious persecutions. But in the 20th century, Polish freedom was especially elusive. As the century dawned, the partitions of Poland had been in existence for over 100 years.

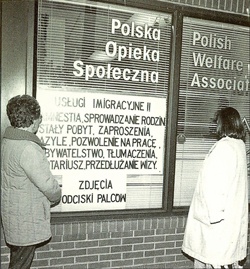

The independence finally regained after World War I lasted only one generation. On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded. Since then, Poland's fate included a long list of atrocities, culminating in martial law from December of 1981 to July of 1983. It is no wonder that America, known internationally as the land of freedom, and Chicago, a center of Polonia in the U.S., would harbor countless immigrants and refugees, all seeking to regain the freedom that is so dear to Poles. It is no wonder that family reunification and promises of a better future continue to attract immigrants, even from a post-Communist Poland. As early as 1948, the Archbishop's Veterans Committee for the Archdiocese of Chicago charged Polish Welfare Association with resettling displaced persons. Consequently PWA staff located housing, found employers, provided emergency services and taught the nuances of the American way of life. As history moved into the mid-70's and beyond, newcomers were no longer displaced persons, but rather political refugees. The vast number entering the U.S. made expansion PWA's watchword. PWA had long been situated in the triangle formed by Ashland, Division and Milwaukee Avenues.

Polish Welfare Association south side office at the Rectory of Five Holy Martyrs Church at 4327 South Richmond in 1994.

The Five Holy Martyrs Church was an obvious choice for the Polish American Association to have its location at in 1994/1995 due to its wonderful attributions to Polish immigrants and the Polish community. To this day, the Church teaches the Polish language at “Saturday school” while also observing Polish customs. The bulletin each Sunday is published in both English and Polish along with the Eucharist being celebrated in Polish during alternate weekdays and in two masses on Sundays. The importance of keeping the Polish culture apart of the Church is clear through the services it provides.

Five Holy Martyrs Church today

The PWA/PAA headquarters on the north side at 3834 North Cicero, purchased in 1985. In 1977, a second office opened on the northwest side of the city. Although it closed within a few years, the present-day facility on North Cicero Avenue is its reincarnation. Purchased in 1985 and financed by the sale of the original facility, it appeared to be sufficient for every activity. That was not to be, however. A southwest office opened just three years later.

Then the Learning Center moved to a separate building in 1994. Finally, homeless outreach offices on Milwaukee Avenue opened only a few months ago. In the mid-70's the first concentrated effort to reach out to other immigrant organizations and to draw help from such groups as the Mayor's Office for Senior Citizens, Catholic Charities and the Jewish Community Center took place. Writing proposals for grants allowed PWA to assist a more diverse population, but also demanded specialization. Furthermore, when the national amnesty program was introduced in 1987, the organization ballooned. The Learning Center started a rapid and monumental growth. Immigration services took on activities far beyond the mere filling out of applications. And social services were still in demand. Today's clients count on Polish American Association for information on revisions of immigration law, social security rulings and implications of welfare reform. PAA is now as likely to place an article in the English press as in the Polish; and both radio and TV play a more prominent role. Youth are served through partnerships with schools. Job training and job placement walk hand in hand. What was good about Polish Welfare Association has been kept; what has required change has been addressed. On the occasion of its name change on March 4, 1996, the organization reiterated its commitment to improve the well being of individuals, to strengthen the community, to be a resource for changing lives. Now, as PAA starts on its march toward a 100th anniversary, it continues to eye the compliment paid to it in Poles of Chicago, 1837- 1937: Although it is the youngest of the Polish welfare organizations, it is destined to be the most extensive and influential in its work. Written at age 15, those words are still both a hope and a goal today.

On March 4, 1996 (Pulaski Day), Polish Welfare Association became Polish American Association. The PAA proudly participated in the 1996 Polish Constitution Day Parade, the firs parade under the new name

POLISH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION CHRONOLOGY OF LEGAL FILINGS

August 16, 1922

Polish Welfare Association incorporates

1201 North Milwaukee Avenue

"to secure the greatest amount of cooperation from the citizens of Polish extraction, to promote the moral and physical welfare of our people; to cooperate with legal agencies and various welfare organizations in the handling of the juvenile and adult delinquents, and to carry on a campaign of education and information directly into the horne to reduce delinquency."

August 3, 1936

Name changed to THE POLISH WELFARE ASSOCIATION OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF CHICAGO

September 4, 1940

Location changed to 1263 N. Paulina Street Room 407

February 15, 1955

Name changed to THE POLISH WELFARE ASSOCIATION

November 29, 1976

Purpose changed: "This organization is organized and shall be operated exclusively for charitable, educational and scientific purposes within the meaning of Section 501 © (3) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954, including such purposes the making of distributions to organizations that qualify as exempt organizations under said Section (or the corresponding provision of any future United States Internal Revenue Law).

March 4, 1996

Name changed to POLISH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION

Click HERE to see see our articles of incorporation since 1922.